Swanwick Star Issue No. 9 (2016)

Yoga and Krishnamurti

All great masters are original, not necessary novel. They are original in the real sense of the word—they are close to the origins. Therefore, they each express truth in their own quite unique way. Krishnamurti spoke of an intelligence beyond thought. He insisted that we need to go beyond knowledge. Although we usually think of knowledge as being a good thing, Krishnamurti emphasized the point that thought is the source of the problem, not the source of the solution. Patañjali, who is said to be the author of The Yoga Sutras, said the movements of the mind are the source of the problem. There is much in common between Patañjali and Krishnamurti, but each one expressed their insights in a unique way.

Sutra 1.2 Yoga is establishing the mind (chitta) in stillness.

The literal translation of this sutra, “Yoga is the stopping of the movements (vrittis) of the mind” speaks of the process of yoga to reach the aim of “establishing the mind in stillness.” An accomplished yogi’s mind has a quality of deep silence. Krishnamurti embodied this stillness of the mind. On one occasion, I asked him, “What is the nature of your mind, Krishna Ji? What do you see when you look at that tree?” He was silent for a while and then said, “My mind is like a mill-pond. Any disturbance that is created in it soon dies, leaving it unruffled as before.” Then, as if reading what I was about to ask, he added with the most playful smile, “And your mind, sir, is like a mill!”

The sages have said that when the mind is silent, without distractions, the original state of intelligence or of consciousness, far beyond the capacity of the thinking mind, is present. That intelligence is more aligned to direct perception than to thinking or reasoning. The reminder from Krishnamurti, and from the philosopher Wittgenstein in a different context: “Don’t think; look!” calls us to a perception of the intelligence beyond thought. We may well say that Yoga is for the purpose of cultivating direct

seeing, without imaginings. Yoga leads to gnosis, a knowledge which is quite different from rational knowledge. In fact, Patañjali prefers to call the Real Knower, the Seer.

Sutra 1.3 Then the Seer dwells in its essential nature.

Sutra 1. 4 Otherwise the movements of the mind (vrittis) are regarded as the Seer.

The essential nature, or the true form of the Seer, or the Seer’s own form, is Purusha, the Transcendent Being. Purusha is steady attention without distractions, Conscious Energy or Pure Awareness. When the distractions are removed, the Seer resides in its own true nature. The true Seer is Purusha who knows through the mind. The purpose of Yoga is to refine the mind, so that it can serve as a proper instrument for Purusha. When thinking enters, the mind brings its expectations and its projections; then we cannot see reality as it is.

On one occasion, I had asked Krishnamurti what he thought of something we had been looking at. He said, “Sir, K [that is how he often referred to himself] does not think at all; he just looks.”

In the Indian tradition, the emphasis has always been on seeing, but it is a perception beyond the sense organs, an enlightenment beyond thought, an insight from presence. The real knower is not the mind, although the mind can be a proper instrument of knowledge. The mind needs to become free of the distractions which occupy it and prevent true seeing. The Yoga Sutras emphasizes the need to quiet the mind so that there can be more and more correspondence with the clear seeing of Purusha. Only a still mind can be attentive, and only a still mind can be the dwelling place of Purusha in its own true form. There is a quality of attention and seeing which can bring about an action in ourselves which allows a radical change to take place naturally, from the inside.

I once asked Krishnamurti about the nature of this attention, what he himself called total attention. I said to him, “What I find in myself is that attention fluctuates.” He said with emphasis, “What fluctuates is not attention. Only inattention fluctuates.” We can see from this brief dialogue that for Krishnamurti, attention is the ground, like Purusha, and it does not fluctuate. My question implied that attention can be distracted and can fluctuate—clearly a misidentification of the Seer with the distracted mind.

Patañjali begins with the statement that attention is the main concern of Yoga. Otherwise the Seer—which is above the mind—is misidentified with the instrument of seeing. Steady attention is the first requirement of letting the Real reveal itself to us. The Real is always revealing itself everywhere, but in our untransformed state we are not receptive to this revelation. All the sages of humanity are of one accord in saying that there is a level of reality pervading the entire space, inside us as well as outside, which is not subject to time. The sages call it by various names—such as God, Brahman, Purusha, the Holy Spirit, Allah. However, we are not, in general, in touch with this level because we are distracted by the unreal, by the personal and by the transitory.

Sutra 2.9 Abhinivesha is the automatic tendency for continuity; it overwhelms even the wise.

Freedom from abhinivesha, from the wish to continue the known, is a dying to the self, or a dying to the world, which is so much spoken about in so many traditions. It has often been said by the sages that only when we are willing and able to die to our old self, can we be born into a new vision and a new life. There is a cogent remark of St. Paul: “I die daily” (1 Corinthians 15:31). A profound saying of an ancient Sufi master, echoed in so much of sacred literature, says, “If you die before you die, then you do not die when you die.”

During a conversation about life after death, Krishnamurti said, “The real question is ‘Can I die while I am living? Can I die to all my collections—material, psychological, religious?’ If you can die to all that, then you’ll find out what is there after death. Either there is nothing; absolutely nothing. Or there is something. But you cannot find out until you actually die while living.”

Dying daily is a spiritual practice—a regaining of a sort of innocence, which is quite different from ignorance, akin to openness and humility. It is an active unknowing; not achieved but needing to be renewed again and again. All serious meditation is a practice of dying to the ordinary self.

Direct and impartial perception is the heart of the matter. Seeing what is, not how it should be or could be; just the way it is. But this is not possible as long as the mind is not completely silent. And the mind cannot be completely silent until one is totally free of fear and selfishness. An ordinary person like myself is not free of my conditioning, my fears and ambitions and therefore does not have a silent mind. To me it was clear quite early on in my meetings with him that K’s mind was quite different from mine—and we have his own last statement from his death bed that an energy of that quality will not come again in a body for a long time. However, a part of his upbringing was in the early twentieth century England with a polite nod to democracy and egalitarianism, and he would so often imply that he was no different from the others and that we could all come to the same clear perception as his. To me it just seemed nice manners and not the truth and I expressed some frustration on one occasion. He turned to me and asked, “Sir, do you think the speaker is a freak?” Without any hesitation, I said, “Yes.” Of course, what was intended by the two of us by this word ‘freak’ was different. To me, at that time it did not mean anybody distorted, but ‘someone who is extraordinary and unusual, not like the most of us.’

In more or less a continuation of this exchange, but a little later, it so happened that I was with him in the house of Mary Zimbalist. There on a small table there was a vase with some flowers. I said, “Krishnaji, I am convinced that your mind is very different from mine. What you see is not what I see. Please look at these flowers and describe what you see; I will do the same. Then it will be clear whether our perceptions are the same or different.” He agreed and looked the flowers. “My mind is like a mill-pond. Any disturbance that is created in it soon dies, leaving it unruffled as before,” he said calmly. Then, as if reading what I was about to ask, he added with the most playful smile, “And your mind, Sir, is like a mill!”

Krishnamurti once said during a conversation with me that the intelligence beyond thought is just there, like the air, and does not need to be created by discipline or effort. “All one needs to do is to open the window.” I suggested that most windows are painted shut and need a lot of scraping before they can be opened, and asked, “How does one scrape?” He did not wish to pursue this line of inquiry and closed it by saying, “You are too clever for your own good.”

Here is a very interesting remark of Krishnamurti about yoga:

“The word ‘yoga’ is generally understood as bringing together, tying together. I have been told by scholars that the word ‘yoga’ doesn’t mean that at all; nor all the exercises and all the racket that goes with it. What it means is unitive perception, perceiving the whole thing totally, as a unit, the capacity, or the awareness, or the seeing the whole of existence as one-unitive perception, that’s what it means, what the word ‘yoga’ means.” (Saanen 1971, Seventh Public Discussion).

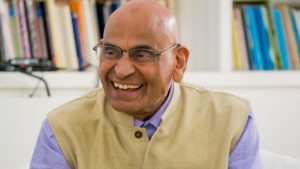

Ravi Ravindra