Swanwick Star Issue No. 8 (2015)

An Important Milestone in the Academic Study of Krishnamurti’s Thought

The International Association for the History of Religions (IAHR) World Congress (August 2015) marked a significant milestone in the development of academic studies on Krishnamurti’s teachings. This is because it was the first time that such a renowned body as the IAHR accepted for presentation an entire panel as well as a paper presentation, thereby acknowledging a growing recognition of Krishnamurti’s place as a religious teacher whose thought elicits and warrants academic research. In order to contextualize and report on this crucial event adequately, a bit of background information is useful.

Many well-regarded books have been written on Krishnamurti’s life, and new publications continue to emerge in the form of biographies and memoirs by individuals about their personal experiences with him. However, scholarly studies on his life and thought have received marginal attention. Nevertheless, over the past decades certain pioneering scholars have written master theses, doctoral dissertations, journal articles, and academic books on Krishnamurti’s thought. These works have often been within the disciplines of education, psychology, philosophy, and religious studies. One of the first academic conferences dedicated solely to Krishnamurti’s thought was held in 1995 (Krishnamurti’s birth centennial) at Miami University in Oxford, Ohio, a renowned centre for the study of Indian philosophy. It was organized by Prof. S.S. Rama Rao Pappu, and Prof. Ninian Smart, one of the pioneers in the discipline of religious studies, delivered a keynote address. Another academic conference, which focussed on Krishnamurti’s influence on education, was organized in 2010 by Dr. Meekashi Thapan, a professor of Sociology at the University of Delhi. There, a keynote address was delivered by Professor Samdhong Rimpoche, former principal of the Central Institute of Higher Tibetan Studies. While each of these conferences were landmark events, by being exclusively focussed on Krishnamurti they did not position Krishnamurti’s thought within the broader world of academia. By contrast, the IAHR 2015 panel and paper mark a pivotal event in which Krishnamurti’s thought was situated within one of the highest profile gatherings for the academic study of religion writ large.

Despite its name, the IAHR is dedicated to the scholarly study of religion using multi-disciplinary approaches including, but not restricted to, history. Scholars may study religion through philosophical, anthropological, sociological, text critical, and a variety of other methods. What is crucial is the effort at objectivity and rigor in studying religious phenomena, teachers, teachings, practices, and beliefs, without any attempt to promote a particular teacher or teaching, and without engaging in apologetics, confessional concerns, or proselytizing. The IAHR was founded in 1950, and is a member of the Conseil International de la Philosophie et des Science Humaines/The International Council for Philosophy and Humanistic Studies (CIPSH) under the auspices of UNESCO. It consists of 42 national and 6 regional member associations and societies, which are international and global in character and scope. The IAHR world congress meets every five years, and this, its XXIst gathering, was held in Erfurt, Germany. As the capital of Thuringia, Erfurt has the distinction of being the birthplace of the Christian mystic Meister Eckhart, and the renowned sociologist of religion, Max Weber. It is also the home of oldest standing synagogue in Europe, established in the 11th century, and thus a very suitable setting for a religious studies world congress.

The keynote address was delivered at the Theatre Erfurt by Hubert Seiwert, professor emeritus of Comparative Religion at the University of Leipzig, and his lecture kicked off the conference that ran from Sunday, August 23 to Saturday, August 29. The Congress attracted over 1300 delegates, including such figures as Donald Wiebe (University of Toronto) and Tomoko Masuzawa (University of Michigan), both well-known for their contributions to theory in the academic study of religion. In such a large event, there were almost always over twenty sessions taking place simultaneously, requiring participants to choose the panels they wished to attend carefully. Inevitably, and typical to such large gatherings, several sessions of similar interest to the same groups were scheduled at the same time slot, compelling the potential audience members to choose just one session of the many possibilities.

The IAHR Congress sessions were held at the University of Erfurt, originally founded in 1392, and both the city and university are proud to have had Martin Luther as their most famous citizen and student. The original university was closed in 1816 and has only been reopened since 1994 after German reunification. The setting was intimate and provided all participants with ample opportunities to interact with each other frequently during and between sessions, as well as in the evenings after sessions over dinner in many of the quaint restaurants scattered throughout the old city.

The idea to attempt to place a panel on Krishnamurti at the IAHR was initiated by Prof. Theodore Kneupper, Professor Emeritus of Philosophy at Slippery Rock University, Pennsylvania. Finding generous support from the Krishnamurti Educational Centre of Canada (KECC), and advice from the Krishnamurti Foundation Trust (KFT), the Krishnamurti Foundation of America (KFA), and Mr. Friedrich Grohe’s team, Prof. Kneupper was able to put together an excellent panel entitled “J. Krishnamurti’s Apophatic Mysticism: its Implications for Religion, Creative Insight, Spirituality, and Individuality,” which was very suitably aligned with the objectives and orientations of the discipline of Religious Studies. Since the maximum number of panel participants permitted was four, Prof. Hillary Rodrigues, Professor of Religious Studies at the University of Lethbridge (Alberta, Canada) proposed a separate, joint paper with a fifth participant, Dr. Chanda Siddoo-Atwal of the KECC. We waited with eager anticipation to see if the proposed panel and paper would be accepted, and were absolutely delighted when we learned that both the panel and the joint paper were. This was a first for Krishnamurti studies within the broad, public, academic venues of the discipline of Religious Studies, and particularly appropriate because despite Krishnamurti’s influence in such fields as psychology, philosophy, and education, he is undoubtedly a highly influential religious teacher.

The IAHR panel started with a paper by Prof. Rodrigues that provided the audience with some background on Krishnamurti’s life. Rodrigues primarily argued that Krishnamurti was far more influential in the new Nondual Spirituality Movement than has been heretofore recognized by scholars. In part, Rodrigues suggested that this was because Krishnamurti’s teachings do not lend themselves to simple categorization, and that Krishnamurti himself was particularly effective in undercutting efforts to link him and his teachings with traditions, lineages of transmission and influences, and so on. This paper provided a context and background allowing the other papers to focus more directly on much more select features of Krishnamurti’s thought.

Professor Theodore Kneupper’s paper illustrated how in his critique of religion, Krishnamurti’s language had modified throughout his long life. Kneupper noted that in the earliest phases, Krishnamurti mostly challenged institutional religions. In later years he moved to distinguishing between the fragmented mind and a wholeness that characterizes “true religion,” and finally emphasized “living meditation” and the negation of thought as potentially transformative of human culture. Kneupper next offered reasonable hypothetical objections to Krishnamurti’s views, but ended with responses to those objections, pointing to the highly effective potential in Krishnamurti’s vision.

Professor Gopalakrishna Krishnamurthy (Principal, Brockwood Park School), whose formal education includes a Ph.D. in Education and a degrees in Physics and Philosophy, presented a discerning analysis of notions of radical negation, which characterize such religious philosophies as Advaita Vedanta, and Nagarjuna’s Madhyamaka Buddhism. With the use of helpful diagrams, Krishnamurthy showed how the approach of radically negating various intellectual categories (e.g., ethical, metaphysical) can erroneously lead one to an essentialist position. In other words, one might mistakenly think that at the end of all the negation, there is still some essential notion that is left standing, which is the target concept to be discovered. Alternately, one might be led through negation to a position of radical skepticism regarding all discourse. Drawing upon Krishnamurti’s teachings, Professor Krishnamurthy used the illustration of how, within a two-dimensional world, a circle may be the best image that one has to “hint” at the reality of a sphere, even though a circle is clearly not a sphere. Thus while the circle is a helpful pointer, it is not what is being pointed to. In the same manner, radical negation, he argued, points to or “hints at” a particular quality of attention, but that the utterances of radical negation can mislead as often as they illuminate.

Professor Alastair Herron (Ulster University), whose areas of expertise include Art History and Communication Arts, presented a critical examination of Krishnamurti’s notion of “creative emptiness”. Herron’s paper inquired into whether there is anything distinctive in Krishnamurti’s approach, which on casual inspection appears to parallel the apophatic (i.e., negation, denial) dimension of certain Eastern religions, such as Daoism and Japanese Zen. In fact, these traditions have also been associated with eliciting creative expression, so evident in material arts such as pottery, painting, and printmaking. However, Herron notes that Krishnamurti does not adhere to any form of traditionalism, which is characteristic of the other systems, and strove to undermine anything like it developing around his own pointers to creative emptiness. Herron suggested but left open the question whether Krishnamurti’s approach actually points to a profoundly creative and compassionate observational awareness that undercuts authority and interpretation.

Those who attended the panel were highly engaged, and some contributed their names to be added to a database of scholars that Prof. Kneupper is currently compiling. These audience members shared their observations, and asked pertinent questions. For instance, a scholar working on New Age religions in Taiwan noted that a series of publications by a New Age press in that country has over half of its titles dedicated to books by Krishnamurti, which is a clear illustration of Krishnamurti’s influence.

On the following day, Dr. Chanda Siddoo-Atwal (Director, Krishnamurti Educational Centre of Canada), and Prof. Hillary Rodrigues jointly presented a paper entitled, “J. Krishnamurti’s Critique of Religion and Religious Studies.” The paper was included in a session chaired by Prof. Richard L. Gordon (Max Weber Centre of Advanced Social and Cultural Studies, Erfurt University) dedicated to theory and method in the study of religion. The joint paper, began with Dr. Siddoo-Atwal presenting a highly empathetic account of three persons, namely, J. Krishnamurti, the theoretical physicist, David Bohm, and the religious studies scholar, Alan Anderson, and how they had influenced her life. Prof. Rodrigues, then spoke about the same three individuals in a relatively objective manner, initially causing the audience some surprise about the nature of the joint paper. The effect was to illustrate aspects of “emic” and “etic” approaches to discussing religious phenomena. Dr. Siddoo-Atwal’s presentation was sympathetic, personal, and evoked some features of an “insider’s” or emic perspective, which is typically marginalized in religious studies. Rodrigues’s etic and “outsider” information presented a contrast, but also illustrated how a deeper understanding of those three key individuals and their influences were probably better obtained by moving past the dualisms of such categories as emic/etic and insider/outsider. This served as a segue into a presentation of Krishnamurti’s critique on the limits of scholarly study, and on the complexities offered to religious studies scholars by Krishnamurti’s notion of religion and the academic study of people aligned with his teachings.

The session was well attended, and both audience members and fellow panelists raised questions or made observations that sometimes synergistically integrated features of all the papers, including the one on Krishnamurti. For instance, Dr. Siddoo-Atwal’s presentation of David Bohm’s approach to inquiry (Bohmian dialogue) elicited questions about breaking through tired and binding scientific paradigms, and how Krishnamurti’s teachings point to the space and silence of the mind, within which fresh insights might be possible in the sciences and all fields of study.

The choice of setting for the IAHR Congress was no accident, because Erfurt enjoyed a rich affiliation with notable figures and edifices in religious history. Moreover, it is very close to the city of Weimar, renowned for such patriarchs of the German Enlightenment as Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and Friedrich Schiller. It seems auspicious, if one could use that term, that the initial discussions to set up an association dedicated to the scholarly study of Krishnamurti’s life and thought began among the Krishnamurti scholars who had travelled to Weimar on a day trip. These, and various other lunch and dinner discussions, as well as those that occurred at times in between throughout the course of our days together, focussed on assessing the successes of the conference presentations, and envisioning ways of moving forward. Prof. Ted Kneupper volunteered to continue his labours to head up the formation of a scholarly association dedicated to Krishnamurti studies, and Dr. Siddoo-Atwal indicated her support through the auspices of the Krishnamurti Educational Centre of Canada (KECC) for such an endeavour. Current proposals include the possibility of holding a scholarly conference at the KECC headquarters in Victoria, British Columbia, creating a website as a nexus for the scholarly association, and initiating an academic journal dedicated to Krishnamurti studies, complying with the highest scholarly standards. Friedrich Grohe’s team has already offered some financial support to initiate the development of the website. Scholars from any disciplinary orientation, who are interested in joining such an association, are urged to contact Dr. Kneupper at theodorekneupper@gmail.com, or the KECC.

Professor Hillary Rodrigues

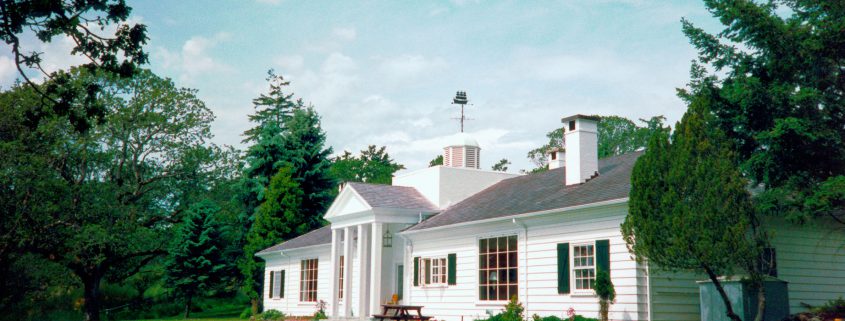

Summer weekend retreat with Prof. Hillary Rodrigues (back row; right of center)