Swanwick Star Issue No. 4 (2011)

Krishnamurti and Advaita

Krishnamurti and Advaita by Professor Hillary Rodrigues

Vedanta is a school of Indian philosophy with ancient origins. It traces its roots to teachings within influential scriptures, notably the Upanishads, which form the latter portion of Vedic literature. A major focus of this philosophy is to question the relationship between the real self (called Atman) and Absolute Reality (called Brahman). Who are we really? What is the nature of this world? And what is our relationship to this mysterious existence? Advaita Vedanta is a stream within Vedanta philosophy that interprets that relationship as non-dual (advaita). In other words, Advaita Vedanta proclaims that a deep investigation into one’s own nature, beyond the superficial identifications that we typically make with our cultures, nations, races, and so on, reveals that Atman and Brahman are one and the same.

There have been many renowned Advaita Vedanta philosophers since the time of the Upanishads, the most famous being the 8th/9th century Indian sage, Shankara. In the last century various teachers have promulgated non-dual teachings, which have sometimes been labeled Neo-Advaita, because the philosophies do not derive from the interpretations of the classical Vedanta texts, and do not insist on their methods. Instead, the teachers point to a sort of experiential realization of the truth of non-dualism. Among these teachers are Nisargadatta Maharaj and Ramana Maharshi.

Krishnamurti did not want his teachings compared to other teachers and their teachings. I think this is because he did not want his teachings to become exclusively subjected to an academic sort of examination. I think K wanted listeners to grasp the essence of what he was saying, when listening to him or reading his words, and in that instant have an insight into the truth to which he was pointing. To go off and think about his teachings, and to compare them to other teachings, while useful for academics like myself, and of interest to everyone’s intellectual curiosities, is not necessarily beneficial in bringing about the transformative psychological insight that Krishnamurti urges us to attain.

Nevertheless, one can certainly find patterns in Krishnamurti’s teachings and demonstrate how these parallel the teachings of the philosophies of liberation. Some have seen similarities between Krishnamurti’s teachings and those of Advaita Vedanta. It would take a volume to delineate all the similarities. However, many traditional followers of the Advaita Vedanta are at pains to point out the differences. I think both groups are correct, because there are many places where Krishnamurti’s teachings converge with those of non-dual philosophies and many places where they diverge from traditional Advaita Vedanta. A simple illustration is to look at Krishnamurti’s statement, “You are the world,” which suggests that the seemingly separate and isolated person is actually one with the broad, fullness of reality. But Krishnamurti also rejects tradition, and paths, and the following of masters and authoritative scriptures, all of which are very much part of the corpus of Advaita Vedanta teachings.

A more interesting activity, I suggest, is a rigorous self-examination of what motivates one to find similarities or to highlight differences between these two teachings. Such an examination might lead to insights into the attachments that one has to either of the two. A pen and a marker have similarities and differences. One can spend much time and energy talking about these and why one has a preference for choosing one over the other. But if one wants to send a letter urgently, such deliberations will not be significant. One will pick up and use whatever is at hand. Krishnamurti seemed to me to be telling us to pick up and use whatever bit of reality is at our disposal, at this moment, because transformative change is something urgent. Conflict is resolved through insight, now, not tomorrow when we have satisfied ourselves that the teachers or teachings we follow are unique, adequately profound, historically venerable, in keeping with the tenets of our religious heritage, and so on. Conflict can be fuelled by minds that apply thinking to satisfy the needs of thought-constructed selves that need to be “right,” and secure in their intellectual preferences.

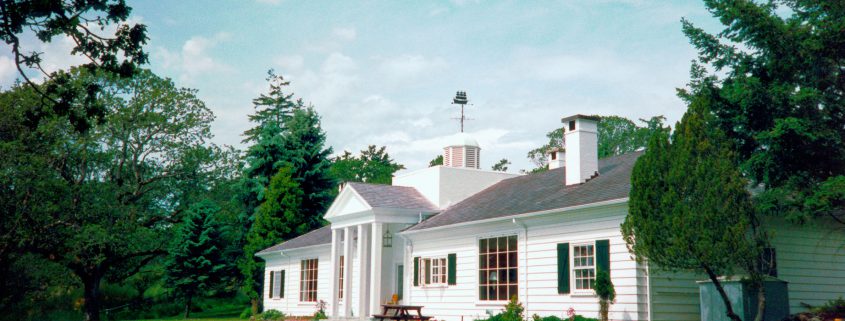

Swanwick Study Centre, Friedrich Grohe [2010]