Swanwick Star Issue No. 8 (2015)

Three Wise Men

My first religious influence was my grandmother, who was a good, spiritually open-minded person born into the Sikh faith. She never forced any rituals, ceremonies, or prayers upon me. My parents were highly educated – my mother and aunt were the first two doctors of Indian origin to graduate in Canada. My father was Dean and an educator at the Punjab Agricultural University and was known for his pioneering research in introducing the European honey-bee (Apis mellifera) into India.

Then, I started going to school. After a few years, my mother and aunt noticed that I was developing certain neurotic tendencies based on competition and comparison at the Catholic School I was attending and decided to start a school based on Krishnamurti’s teachings. It was called Wolf Lake School and they felt that it would benefit other children as well.

My father was against the idea because he saw it as part of the “Hippie Freedom Movement” of the 1960s and 1970s. Just like the East, the West had its own brand of repression and tryranny typified by McCarthyism, Civil Rights inequality, and the Vietnam War, that these young people were revolting against in America which set the whole stage for someone like K. to make an impact on society. However, my father and K’s critics could not have been more wrong about J. Krishnamurti, who had dissolved The Order of the Star and rejected organized religion, as having a “Laissez Faire” attitude towards education.

When we finally met, I was near the beginning of my life and K. was nearing the end of his, but he retained something so unspoilt and child-like that one was immediately drawn to him. His vision of education was that each child should develop their full potential without the shadow of competition and comparison to destroy their spontaneity. As a teenager at Brockwood Park School, I met another student who had been at Summerhill, but he said nobody there really seemed to care. Everything in life was an exploration according to K. – at the academic level and at the spiritual level. Thus, a lot of discussion between students and teachers, students and students, teachers and teachers went on at his schools ranging from lessons to personal relationships to K’s teaching which was basically for each person to be their own guru in learning about oneself, one’s hopes, one’s desires, one’s motivations – in effect, to recognize all that makes one mediocre and is an impediment to one’s inward flowering. It was a very liberating experience to live in a community that encouraged this sort of self-inquiry for a young person, because I think it is the natural preoccupation of the young to want to discover all about themselves. Moreover, it engendered a caring and nurturing atmosphere.

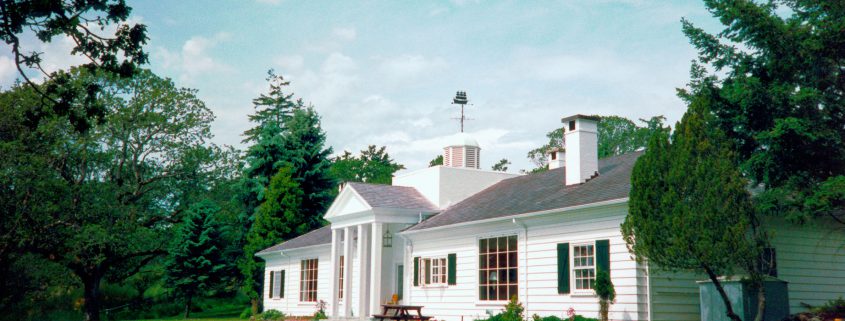

K’s approach to education benefitted me a lot in my undergraduate studies making me thrill in the joy of questioning and exploring things. I always carried that sense of excitement with me which made learning new things such a tremendous pleasure. However, this approach can only take you so far and by my twenties, I felt ready for something more. K. was old and frail and seemed tired out at times and to lack the energy for students, now. Dr. David Bohm, the world renowned theoretical physicist, was younger and had visited Brockwood sometimes for student discussions. He had participated in a number of taped dialogues with K. and others. I got to know him in Canada when I was a graduate student and he would come up for dialogue groups in the summer at the school, which was now an adult centre called The Swanwick Centre. He had developed a very special approach to “dialogue” after years of discussions with K. He felt that K’s teaching could be refined and distilled by the diligent self-inquiry of a committed group of people together. The “energy” to explore could be magnified if it involved a number of serious individuals rather than just one – he was passionately convinced that this was the way forward. It did seem to work for awhile – a great impetus and excitement was generated just as it had been during the establishment of the K. schools in the sixties and seventies. But, eventually, this movement lost its momentum, too, even though, a real sense of community that expanded on K’s vision had been initiated in Canada and America.

David Bohm’s main point was that in dialogue we should examine the underlying assumptions with which we approach everyday life like true scientists, who must question the basis of their minutest beliefs. This had great appeal for me being a science student and he convinced me to continue with my scientific studies at a time I had begun to question my own purpose. The “Dialogue Movement” did not really survive his death, though. We started to find that it was too easy for the group-dialogue proceedings to be “hijacked” by certain individuals with their own personal agendas. There was also the danger of getting into a rut as one might in any relationship at these meetings.

Allan Anderson entered my life suddenly and mysteriously after David died. He came as a breath of fresh air and there was an immediate affinity between us, perhaps, because we both wrote poetry. Allan had done a series of dialogues with K. which he felt had deeply transformed his understanding of life. He was a Professor of Religious Studies at San Diego at the time.

He and I started to have talks on the telephone about K. in the context of many other religious teachings and philosophies over a period of about ten to fifteen years. These have been collected in a work called “The Bird in the Verandah”. The inspiration for this title and what became the theme of our talks is a bird that gets caught in a glass verandah and, initially, cannot find its way out. A terrible struggle ensues. Then, after a pause, two other birds alight and show it there is a way out between the glass sheets and that it has always been there. Finally, the trapped bird understands its freedom.

I told him it was like my Bible or the Upanishads in which the essence of all spirituality was held for me as we delved into the deepest mysteries of mankind on our own terms, without the “K. rhetoric” or “K. terminology” which had come to epitomize so many clever, but meaningless conversations in the K. world. Thus, it all had to be re-discovered by each seeker in the depths of their own soul as K. himself had always insisted. In effect, K. and everything associated with K. had to be rejected in order to reach a new understanding of his teaching.

Allan was retired and leading the life of a Zen master and I was like his pupil and we were exploring together, relentlessly, having rejected the “K. culture” that had been built up by the people around him which simply replaced the restrictive, inflexible constructs of the Theosophists. We really had to break free of all this in order to reach further into infinity.

Near the end, Allan said that he did not need to meditate per se as a practice because he had attained a harmonious relationship with himself and that “listening” was the key. It is one’s relationship to consciousness that matters; one must “listen” in order to plummet its depths which has so many shades and textures of the thinker and thought before the final silence of Intelligence – and, to know the content of one’s consciousness in that silence.

Strangely, sometimes, I would say to Allan that I felt a responsibility to share what we had explored together in our discussions with others and I could just feel him smiling like the Cheshire cat at the other end of the line. He was quite fond of quoting “Alice in Wonderland”.

[Re-printed in part from a paper presented by Chanda Siddoo-Atwal (Ph.D.) with Professor Hillary Rodrigues at the 21st World Congress of the International Association for the History of Religions (IAHR) and dedicated to the memory of Dr. Allan W. Anderson, Professor Emeritus Religious Studies, San Diego University.]